Brief Professional Biography

William L. White is an Emeritus Senior Research Consultant at Chestnut Health Systems / Lighthouse Institute and past-chair of the board of Recovery Communities United. Bill has a Master’s degree in Addiction Studies and has worked full time in the addictions field since 1969 as a streetworker, counselor, clinical director, researcher and well-traveled trainer and consultant. He has authored or co-authored more than 400 articles, monographs, research reports and book chapters and 20 books. His book, Slaying the Dragon – The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, received the McGovern Family Foundation Award for the best book on addiction recovery. Bill was featured in the Bill Moyers’ PBS special “Close To Home: Addiction in America” and Showtime’s documentary “Smoking, Drinking and Drugging in the 20th Century.” Bill’s sustained contributions to the field have been acknowledged by awards from the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, NAADAC: The Association of Addiction Professionals, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and the Native American Wellbriety Movement. Bill’s widely read papers on recovery advocacy have been published by the Johnson Institute in a book entitled Let’s Go Make Some History: Chronicles of the New Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement.

Biography

William L. (“Bill”) White, Emeritus Senior Research Consultant at Chestnut Health Systems, graduated magna cum laude from Eureka College and obtained a Master’s Degree in Psychology / Addiction Studies from Goddard College.  Japan Lecture Tour 2007

Japan Lecture Tour 2007

He has worked full time in the addiction treatment field since 1969 as a streetworker (indigenous outreach worker and community organizer), counselor, clinical director, administrator, and research associate. His early employers include the Illinois Department of Mental Health, several local addiction treatment and mental health agencies, the Illinois Dangerous Drugs Commission, and the Midwest training center of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. He was one of the founding staff members of Lighthouse (Chestnut Health Systems, 1973) and, following positions in Chicago and Washington D.C., returned in 1986 to start Chestnut’s research and training division. He has provided training and consultation in 45 states and in Asia and Europe.

Lecturing in the UK 2009

Lecturing in the UK 2009

A visible fixture on the addictions summer school and conference keynote/workshop circuit for more than two decades, Bill recently refocused his professional activity on recovery-focused consultations and professional writing.

Bill has authored or co-authored more than 400 articles, monographs, research reports and book chapters as well as 20 books. His articles have been published in such peer-reviewed journals as:

- Addiction

- Addiction Research and Theory

- Advances in Dual Diagnosis

- Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research

- Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly

- American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse

- American Journal on Addictions

- American Journal of Community Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice

- Contemporary Drug Problems

- Drug and Alcohol Dependence

- Drug and Alcohol Review

- Employee Assistance Quarterly

- Evaluation and Program Planning

- IN SESSION: Journal of Clinical Psychology

- International Journal of Self Help and Self Care

- Journal of Addictive Diseases

- Journal of Addiction Medicine

- Journal of Addiction Treatment

- Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence

- Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research

- Journal of Child Maltreatment

- Journal of Drug Issues

- Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery

- Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences

- Journal of Psychoactive Drugs

- Journal of Substance Abuse and Alcoholism

- Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment

- Journal of Teaching in the Addictions

- Offender Substance Abuse Report

- Perspectives: The Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal

- The Psychology of Addictive Behaviors

- Public Health Reviews

- Recent Developments in Alcoholism

- Religions

- Social Work

- Substance Abuse

- Substance Use and Misuse

Bill has also written extensively for the many professional trade journals to reach those working on the front lines of addiction treatment, including:

- Addiction Professional

- Behavioral Healthcare

- Behavioral Health Management

- Counselor (more than 75 articles)

- EAP Digest

- Employee Assistance Report

- Student Assistance Journal

- Treatment & Recovery Industry Insider

- Visions: National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers

- Addiction Today

- Advances in Addiction & Recovery

Bill’s book, Slaying the Dragon – The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America, received the McGovern Family Foundation Award for the best book on addiction recovery. Bill has also authored or co-authored books/monographs detailing the histories of the New York State Inebriate Asylum, National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD), National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, and the history of recovery among Native American tribal communities. His other books focus on such diverse subjects as promoting organizational health of addiction treatment institutions, ethical issues in addiction counseling, American cultures of addiction and recovery, management of drug surges (oxycontin, methamphetamine), and the Chicago model of AIDS case management. He has also co-authored books to coach future generations of addiction counselors in the arts of professional training and writing.

Bill has been a visible recovery advocate. He is the past-chair of Recovery Communities United and has served as a volunteer consultant to Faces and Voices of Recovery since its inception in 2001. He has worked with recovery advocacy organizations all over the United States and has keynoted several recovery summits, including the historic St. Paul Recovery Summit in 2001. Bill’s widely read papers on recovery advocacy were published by the Johnson Institute in the book Let’s Go Make Some History: Chronicles of the New Addiction Recovery Advocacy Movement. He has also served on the board of the Betty Ford Institute, the International Advisory Board of SMART Recovery,  Dr. DuPont Presenting ASAM Award the Scientific Advisory Board of Phoenix House, the board of Wellbriety for Prisons, Inc., the Advisory Council of the Association of Recovery Schools, and the editorial boards of Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, Counselor and Student Assistance Journal.

Dr. DuPont Presenting ASAM Award the Scientific Advisory Board of Phoenix House, the board of Wellbriety for Prisons, Inc., the Advisory Council of the Association of Recovery Schools, and the editorial boards of Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, Counselor and Student Assistance Journal.

Bill has also been involved in a number of major public education efforts. He was featured in the Bill Moyers’ PBS special Close To Home: Addiction in America, Showtime’s documentary Smoking, Drinking and Drugging in the 20th Century, Bill W. and The Anonymous People, and served as a consultant to the HBO special Addiction.

Bill’s sustained contributions to the field have been acknowledged by awards from the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, NAADAC: The Association of Addiction Professionals, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, Harvard Medical School / Department of Psychiatry, and the Native American Wellbriety Movement.

With Rita in Japan 2007 Bill spends his leisure time reading (mysteries/thrillers), tending his bamboo garden, searching out new restaurants in Southwest Florida with his wife Rita, and anticipating visits with his children Alisha and Troy.

With Rita in Japan 2007 Bill spends his leisure time reading (mysteries/thrillers), tending his bamboo garden, searching out new restaurants in Southwest Florida with his wife Rita, and anticipating visits with his children Alisha and Troy. Bamboo Garden 2008

Bamboo Garden 2008

Career Reflections

2017 Interview by Dr. Andrea Barthwell in Counselor

Biographical Data

| Year |

Milestone |

| 1969 |

Graduated magna cum laude, Eureka College, Psychology, Sociology & History |

| 1977 |

M.A., Psychology/Addiction Studies, Goddard College |

| 1967-1969 |

Psychiatric Technician, Illinois Department of Mental Health |

| 1969-1971 |

“Streetworker” & community organizer, Illinois Department of Mental Health |

| 1971-1972 |

Director of Adolescent Services, McLean County Mental Health Center, Bloomington, IL |

| 1973-1976 |

Counselor, Clinical Director, Project Lighthouse (residential addiction treatment program), Bloomington, IL |

| 1976-1978 |

Dangerous Drugs Specialist, Illinois Dangerous Drugs Commission, Chicago, IL |

| 1978-1979 |

Deputy Director, Regional Training Center, National Institute on Drug Abuse. |

| 1979-1982 |

Senior Research Associate, Health Control Systems, Washington, D.C. (National Drug Abuse Center) |

| 1982-1986 |

Director, Addiction Treatment Center, St. Mary’s Hospital, Decatur, IL. |

| 1986-1993 |

Director of Training and Consultation, Chestnut Health Systems / Lighthouse Institute |

| 1994-2012 |

Senior Research Consultant, Chestnut Health Systems / Lighthouse Institute |

| 2013-present |

Emeritus Senior Research Consultant, Chestnut Health Systems / Lighthouse Institute |

Conversation with William L. White

Conversation with William L. White

Addiction (A): Tell us something of your personal background before you entered the addictions field.

William L. White (WLW): I was born in 1947 to parents who met while both were serving in the US Army in World War II. My father was a construction worker and my mother was a nurse. I had a large family with more than 20 blood, adopted and foster siblings who shared the close intimacy of a small rural Illinois community. My parents placed great importance on education, having both come from families in which such achievement was routinely denied by life circumstances. I was fortunate to obtain scholarships to Eureka College, a small liberal arts school in Illinois. It was there that I developed a love for learning and an early interest in psychology, sociology and history. There were several influences from these early years that shaped aspects of my subsequent professional life: a public service ethic inspired by my own family and a young charismatic president (John Kennedy), a deep commitment to social change spawned by the American civil rights movement, and a love of writing. As I began my professional life, there was also a sense that my young life had been lived inside a cocoon. I have spent more than four decades since appreciating anew what I experienced within that cocoon at the same time I have fought to escape its limitations.

Finding the Addiction field

A: Did you find the addiction field or did the addiction field find you?

WLW: I am one of a legion of people in the late 1960s drawn to an emerging treatment field in the United States out of our own personal or family recovery experiences. That background stirred my early courtship with the field, but other experiences generated my long-term commitment to this work.

A: Could you provide an example of such an experience?

WLW: My first employment in the field was in 1967 with the Illinois Department of Mental Health. During that era of deinstitutionalization, one of my responsibilities was to tour the back wards of aging state psychiatric hospitals to screen alcoholics and addicts for potential community placement. Those visits afforded me a poignant opportunity to witness the care of the addicted in the decades before the emergence of community-based treatment. The depraved conditions in those institutions stirred my activism, as did my interviews and reviews of decades-old charts documenting prolonged institutionalization, bizarre and near-lethal withdrawal procedures, coerced sterilizations, “shock therapy,” psychosurgery, and drug insults of unending varieties. Forty years later, I can vividly recall the leather restraints and straight jackets, the hydrotherapy tubs, the over-crowded wards, the stench of urine and paraldehyde and the feeling of utter hopelessness that permeated those institutions. If I had entered the field only a few years later, I would have had no real sense of the horrid conditions that preceded modern addiction treatment.

A: What addiction treatment resources existed at the community level at that point in time?

WLW: There were fledgling alcoholism programs, therapeutic communities and methadone programs, but there were no specialized addiction treatment services in most American communities. In the cities in which I was working, I couldn’t even get alcoholics admitted to local hospitals for treatment of acute trauma because of morality clauses in hospital by-laws that prohibited the admission of alcoholics. Institutional ownership of alcohol and drug problems in those years rested with the criminal justice system, so much of my early outreach work was in the city drunk tanks and the county jails. The only welcome sign and haven of comfort for the addicted in most cities was inside the meeting rooms of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

A: Is there an incident that typifies your early work during this period?

WLW: There is one that immediately comes to mind. I helped get a man released from the drunk tank of a local city jail, connected him to a local AA group and offered daily support to him and his family. He did amazingly well for a few months considering the severity and duration of his alcoholism. It was the week of Christmas when, depressed over the gifts he was unable to provide for his wife and children, he sought the balm of an offered bottle. He was jailed later that day for public intoxication and hung himself during the night in the same cell in which I had first met him. Such suicides were common in those years. When I stood before his body and met later that day with his family, I was overwhelmed by my own ineptness and the meager resources I had been able to muster in my offer of assistance. There were no addiction-trained physicians, no detox units, no treatment programs, no trained addiction counselors. I was enraged that this man had to die in despair in such a despicable place. I think my commitment to spend my life working in this field began that day.

A: Your work to help found Chestnut Health Systems was an early product of that commitment. How did this come about?

Streetwork 1971

Streetwork 1971

WLW: I worked as a streetworker (what today we would call an outreach worker) and community organizer for the state mental health department and a local mental health center in the early 1970s. The needs I was witnessing as a streetworker, including my outreach in the jails and hospital emergency rooms, informed the types of services I was trying to organize. This led to helping develop one of thousands of local alcoholism councils that were popping up in these years. Landmark legislation was passed in the early 1970s that channeled federal dollars through the states to local communities to plan, build, staff, and operate addiction treatment programs. After almost 3 years of planning, our local council received word in 1972 that we would be funded to open the community’s first treatment center. I was invited to work as a counselor at Lighthouse, which was later rechristened Chestnut Health Systems. Within months, I assumed the clinical director position. I should note that advancement in those years was as likely to result from surviving the high staff casualty rate as from one’s competence.

A: You have suggested that the exploitation of recovering people is an untold story in the early history of modern addiction treatment.

WLW: We need to acknowledge the contributions recovering people made in birthing and sustaining the field in the days before addiction treatment came of age. There were few guidelines in the 1960s and 1970s on how to screen, select, orient, train, and supervise the mostly recovering people recruited to work within newly arising treatment programs. Those hired were paid a pittance, worked unconscionably long hours, and were often discarded when they succumbed to the stress placed upon them. Even among those who survived, many were later pushed out of the field in the rising tide of professionalization. As a field, we have not adequately honored the sacrifices and contributions of that generation of workers.

A: How would you describe the clinical philosophies of treatment during the early 1970s?

Lighthouse 1973

Lighthouse 1973

WLW: There were few well-developed models of treatment. When Lighthouse opened its doors, we drew from two traditions. Like thousands of others, we visited Hazelden in Minnesota and met with Dan Anderson, Gordy Grimm and Harry Swift who graciously shared everything about the inner workings of the Minnesota Model. We also drew from Chicago’s Gateway House, a second generation therapeutic community, whose leaders were equally gracious in sharing the details of their clinical operations. It’s important to note that there were two addiction fields at this time. There was an alcoholism field and a drug abuse field. Lighthouse faced a unique challenge because we were committed to treating alcoholism and drug addiction in the same facility and through an integrated philosophy of treatment and recovery. Dr. Don Ottenberg of Eagleville Hospital in Pennsylvania was championing a similar approach and offered us considerable support. Our advocacy for the integration of these two fields drew a lot of criticism in those days.

The Chicago / Washington DC Years

A: In 1975, you made a decision to return to school. How did you come to this decision?

WLW: All of us reach stuck points in our careers that force us to reevaluate our relationship with our chosen field. I reached such a point in 1975 and decided, as an alternative to leaving the field, to get into the field even deeper. This sparked two further decisions. First, I enrolled in an addictions studies program at a time few such programs existed in the United States. I was able to arrange a Master’s program in Addiction Studies through Goddard College that allowed me to use Dr. Ed Senay as my primary mentor. Dr. Senay was one of the founders of the Illinois Drug Abuse Program and a professor at the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Chicago. My professional maturation began under his guidance. The second decision I made was to expand my experiential knowledge by gaining exposure to different types of treatment modalities, treatment in different cultural contexts and different specialty roles within the field. This led to my relocation to Chicago and a position with the Illinois Dangerous Drugs Commission. My work there provided an understanding of the larger state and national infrastructure of the field and expanded my knowledge and skills in planning, policy development, research and training. My work at the Dangerous Drugs Commission led to my accepting a position as Deputy Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s midwest training center and an eventual transfer to Washington DC where I first gained exposure as a national trainer.

A: You have often talked about the disconnection between policy and planning and the frontline realities of addiction, treatment and recovery. Was that an observation drawn from your Chicago and Washington DC years?

WLW: Yes. My goal for working in Chicago and Washington DC was to learn the inner workings of the state and federal addictions policy institutions. Some incredibly talented individuals crossed my path inside these organizations, but I was struck by the breach between these organizations and the front line realities of addiction and addiction treatment. I learned that the whole can be less than the sum of its parts. The technical and administrative skills possessed by individuals working in these state and federal agencies were impressive but, when added together, did not result in agencies that had anything other than a veneer-thin understanding of addiction, treatment and recovery. Years later, I joined others calling upon these organizations to increase the depth of that knowledge and to truly become recovery-oriented systems of care.

A: Your work within the NIDA’s National Training System afforded opportunities to work with front line counselors from all over the United States. What did you take from this experience?

WLW: This was the first time I began to see myself as serving the larger field rather than a particular program or a particular community, and I got to know the enormous diversity of how treatment was conducted across the United States. I began to define the field in terms of common themes heard in my travels. I would listen and ask myself, “What does this personal or local story tell me about the evolving character of the field?” Working with the NIDA and NIAAA training systems in those years was a wonderful experience. I learned a lot about workforce and leadership development from visionaries like Dr. Lonnie Mitchell and George Zeiner. It was exciting being part of the effort to recruit, train and professionalize America’s addiction treatment workforce. During this time, I refined the presentation skills that would keep me on the lecture circuit for the next two decades.

Treatment in the 1980s

A: In 1982, you returned to Illinois to direct a hospital-based addiction treatment program. How would you describe the state of treatment in those years?

WLW: This move was a conscious effort to deepen my clinical leadership skills, and it was a great time to do it. The early 1980s were the glory days of addiction treatment—the height of the destigmatization, decriminalization and medicalization of alcohol and other drug problems in America. This was the pinnacle of recovery as a cultural phenomenon in America—a time when it was cool to be in recovery. Accreditation standards for treatment programs and new addiction counselor certification systems in the 1970s had legitimized addiction treatment. Twelve Step programs and their alternatives were growing explosively. We even had a First Lady of the United States (Mrs. Betty Ford) talking publicly about her recovery from addiction to alcohol and other drugs. It was an amazing time. At the clinical level, it was a period of great innovation—increased sophistication in clinical assessment, the development of specialized programs for women and adolescents, and the proliferation of family programs, to name just a few areas. And yet at the larger level, forces were unleashed that would stir a backlash against the field. While treatment reached the mainstream in an unprecedented way in the 1980s, this period marked the rapid commercialization of addiction treatment. Private and hospital-based programs proliferated and consumed all the dollars that the insurance industry was willing to briefly invest in addiction treatment. In this environment, alcoholics and addicts became a crop to be harvested for financial profit. The abuses inside the treatment industry subsequently led to the erosion in treatment benefits and an aggressive system of managed care that led to the collapse of many programs and radically altered the character of addiction treatment in the US. The image of the field has still not fully recovered from such abuses.

The Lighthouse Institute and Early Books

A: What led to your return to Chestnut Health Systems in 1986 and the founding of the Lighthouse Institute?

Training 1988

Training 1988

WLW: In 1986 at the hospital where I was working I was struggling without success to create a department of behavioral medicine with its own research and training institute. At a conference I was attending, I shared my frustration in failing to achieve this goal with Russ Hagen, who I had hired in 1974 and who had gone on to lead Chestnut Health Systems into an organization far beyond anything I could have ever envisioned. Russ called me a few weeks later and invited me to return to Chestnut to create a research and training division. I accepted and became the first staff person in Chestnut’s Lighthouse Institute. Within a few years, I was joined by Mark Godley, Susan Godley, Mike Dennis, Christy Scott and other senior staff whose projects have brought the Lighthouse Institute to its current status. As more experienced and skilled researchers arrived, I continued to work on some research projects but focused most of my time delivering addiction-related training and consultation services throughout North America.

A: Your first research project at the Lighthouse Institute continued for more than fifteen years and exerted a great influence on your professional life. Could you highlight some of what you learned from this project?

WLW: In 1986, I was asked to evaluate Project SAFE (Substance Abuse Free Environment), an innovative project that mobilized the combined resources of addiction treatment and child welfare agencies in more than 20 Illinois communities to intervene with addicted women with histories of abuse or neglect of their children. I served as the lead evaluator of that project until 2002 and was forced to rethink much of what I thought I knew about addiction and recovery. I owe many of my later contributions to what I learned from hours spent interviewing those recovering women and their counselors and outreach workers. To give one example, my traditional training had led me to the belief that motivation for recovery was a pain quotient, that recovery was ignited when the pain of continued drug use surpassed the pain of severing the cherished drug relationship. When I expressed this one day, a Project SAFE outreach worker responded angrily, “Bill, my clients don’t hit bottom; they live on the bottom! Bottom is the norm for them. They have more pain in their lives than you could ever comprehend. The major obstacle to their recovery is not the absence of pain; it is the absence of hope!” This was one of innumerable lessons I would learn from the remarkable women involved in Project SAFE. My later writings on gender-specific treatment, client engagement, and family-centered care all drew heavily from my Project SAFE experience.

A: After almost twenty years working on the front lines, you began what has been a prolific writing career in the field. Was this a difficult transition?

WLW: It was difficult because there was no source of guidance about how to write and publish in this field. Technical and even ethical aspects of such writing all had to be acquired by trial and error unless you were fortunate enough to be coached by one of the field’s elders, and even that mentoring was often not comprehensive in its scope. The International Society of Addiction Journal Editors recently released Publishing Addiction Science: A Guide for the Perplexed [1]. This work is an invaluable tool that I wish would have been available when I embarked on my writing career in the 1980s. Anyone serious about writing in this field should own and regularly consult this Guide.

A: Shortly after you returned to Chestnut you published your first book, Incest in the Organizational Family. What was the source of inspiration for this book?

WLW: It was a very personal form of sense-making. I had helped build some very innovative programs in the 1970s, but then witnessed some of those programs implode at the very time they were receiving considerable external recognition. I saw similar destructive organizational processes in my consultation work with many addiction treatment programs. There seemed to be a propensity for addiction treatment programs to become closed incestuous systems marked by charismatic leadership, ideological extremism, professional and social isolation, and abuses of power that injured both clients and staff. I wrote my first book to illuminate this process and to describe strategies that could prevent or reverse it. I attributed much of this closure process to the derived stigma attached to addiction treatment institutions and the people who work in them [2].

A: How did you come to write the book Critical Incidents: Ethical Issues in the Prevention and Treatment of Addiction?

WLW: Because of my tenure in the field, I was often asked for advice about difficult situations that would arise in the life of local treatment programs. Many of these situations involved complex ethical as well as clinical and managerial issues. By the early 1990s, I was concerned about the growing prevalence of ethical breaches in the field and the inadequate level of training our workforce had received in ethical decision-making. There were our early codes of ethics and LeClair Bissell and James Royce had done a great service to the field by writing the introductory primer, Ethics for Addiction Professionals [3], but I felt we needed an ethics casebook that provided a model of ethical decision-making and used real ethical dilemmas to mark the ethical terrain of the field. Critical Incidents was released in 1993, and I think it did achieve its goal of heightening the ethical sensitivities and improving ethical decision-making of addiction counselors [4]. I wrote the book that I wish someone would have given me when I first entered the field. I am delighted about its use as a textbook in addiction studies programs and that the ethical decision-making model it contains has been applied to everything from clinical research to addiction publishing [5,6].

A: The second edition of Critical Incidents included legal annotations provided by Renée Popovits. How did you come to the decision to add these?

WLW: When I was working on the first edition in the late 1980s, it seemed to me that the treatment field was becoming addicted to money and regulatory compliance. I feared that including discussions of legal issues would reduce the question, “Is it ethical?” to the question, “Is it legal?” As a result, I limited the legal discussions in the first edition. By widely disseminating the first edition, I think the field was prepared for a second edition that integrated discussions of ethics and law within the book’s 200 case studies. It also took some time to find a collaborator who had extensive experience dealing with legal issues in addiction treatment. Renée Popovits brought that experience and made significant contributions to the new edition.

A: You also wrote a book on AIDS case management in the early 1990s. How did that project develop?

WLW: That project grew out of my donating addiction-related training services to the AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC) to support its consortium model of AIDS case management. The growing interest in replicating this model in other communities prompted a decision by the AFC board to prepare a book on their model. They asked me to take on that project, and I spent more than a year interviewing people with AIDS and their families as well as a large number of AIDS case managers in Chicago. The product of that effort was Voices of Service, Voices of Survival: AIDS Case Management in Chicago. My work on the book and my broader work with the AFC were attempts to offer some personal response to the devastation of the early AIDS epidemic [7].

Slaying the Dragon

A: You are perhaps best known for Slaying the Dragon, your work on the history of addiction treatment and recovery in America. How did this work begin?

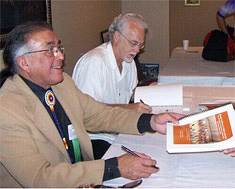

Book Signing 1999

Book Signing 1999

WLW: I had worked in direct services for almost a decade before stumbling onto the existence of earlier periods of addiction treatment. I felt somehow cheated that such knowledge had not been passed on to me and became curious about the early history of treatment and recovery support groups. I began researching this history in the mid-1970s with the thought that I would write an article on this history for addiction counselors. That research ended up spanning the next twenty years of my life. Every time I thought I had a complete grasp of this story, I stumbled onto a previously unknown episode within the field’s history. I hope there will be other histories that will surpass what I have created, but I’m very pleased to have written the first comprehensive history of the field and to have published it in a way that it has remained affordable to the lowest paid workers in the field [8].

A: You must have found that research quite enjoyable to have sustained it over that many years.

WLW: It became one of the professional loves of my life. First, there was the excitement of historical discovery, particularly in the archival research. I vividly remember unwrapping a document in the Keeley Archives at the Illinois State Historical Society that was still in the original packing papers in which it had been shipped many decades earlier. Inside the packing papers was a log book documenting the histories of more than 130 physicians who had been treated for addiction and had then been hired to work as physicians in one of the more than 120 Keeley Institutes. As I stared at the pages of this document, I knew I had discovered an important and previously unknown chapter in the early history of addiction medicine. It was an amazing feeling. There were also many recent chapters of the history of treatment, such as the rise and fall of Parkside (the largest provider of addiction treatment services in the US prior to its collapse in 1993), that could only be acquired through interviews with key figures. That gave me the opportunity to interview some of the modern pioneers of addiction treatment in America. I valued the information they provided me, but I also grew from my personal encounters with these remarkable individuals. My interviews with people like Dan Anderson, Vincent Dole and David Deitch exerted a profound influence on my own commitment to the field.

A: Your contributions in writing the history of treatment and recovery in America have been blessed by some special mentors. Could you describe their role?

Dr. Ernie Kurtz 2008

Dr. Ernie Kurtz 2008

WLW: The most important of these mentors has been and still is the Harvard-trained historian Ernie Kurtz. I knew of Ernie’s definitive history of AA [9] and contacted him in the early 1990s with a request that he review the four chapters I had drafted on AA for Slaying the Dragon. That initial contact grew into a sustained mentorship of nearly all of my subsequent history work. Ernie emphasized the importance of telling a story chronologically and showed me how to tell a story in context and to personalize and localize a story. He taught me to provide evidence for the accuracy of each story and to carefully separate fact from conjecture.  Dr. David Musto 1996

Dr. David Musto 1996

He encouraged me to tell a story from different perspectives. And he told me to stay in contact with my reader—to keep the reader eager to turn the page to find out what would happen next [10]. He also taught me a great deal about interviewing, particularly how to work through weak or distorted memories, and he connected me to a larger network of historical scholars within the addictions arena. Much that I have achieved as a treatment and recovery historian I owe to my mentorship with Ernie Kurtz. Other mentors, role models, and important sources of encouragement for my historical writing have included David Musto, David Courtwright, David Lewis, Tom Babor, Tom McGovern, Bob DuPont, and Griffith Edwards.

A: You have recently chronicled the history of what you have christened the New Recovery Advocacy Movement in the US. How would you describe your role in this movement?

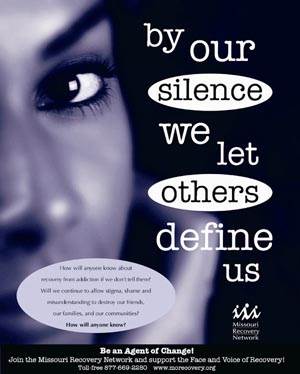

WLW: Recovery Advocacy Poster

Recovery Advocacy Poster Early Recovery March

Early Recovery March Recovery Advocates in Tokyo 2007

Recovery Advocates in Tokyo 2007

It is a role that has evolved over the past decade. I was interviewed in the spring of 1997 by Bill Moyers for the PBS special Moyers on Addiction–Close to Home. In that interview, I predicted a potential surge in organizing efforts by recovering people and their families in response to the restigmatization and renewed criminalization of alcohol and drug problems that had occurred through the 1980s and 1990s in the US. Within two years of that interview, new grassroots recovery advocacy organizations were forming and many of the local affiliates of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD) were undergoing renewal processes to revive their advocacy roots. I tried to both document and encourage these developments. Since recovery advocates first came together in October 2001 to launch a broad scale national movement, I have volunteered time to NCADD, Faces and Voices of Recovery (FAVOR), the Johnson Institute, and numerous local recovery advocacy organizations as a speaker and writer. My recovery advocacy papers have been posted at the FAVOR web site and have been recently published in book form with proceeds going to support this movement [11].

A: how do you square your role as dispassionate scholar with that of activist?

WLW: There has clearly been tension between my aspirations for objective scholarship and my activist role in this movement. I am without question a historian with an agenda. I worried that this activist stance might violate standards of scholarly detachment and objectivity until I ran across an essay by Aurora Levins Morales entitled “The Historian as Curandera” [12]. She suggests several strategies for the activist historian: Tell untold or undertold stories, identify misinformation and expose it, ask provocative questions, explore non-traditional sources of historical evidence, portray stories that reveal people as actors rather than victims, reveal complexities and ambiguities and make history accessible to real people. Her essay conveyed more articulately than I ever could the role I was seeking through my historical research and writing. My goal is to use history to change people’s lives and to elevate the professional field that has been such an important part of my life. The stories I have uncovered are informative and entertaining, but my interest in them is primarily in the lessons they convey—lessons that can influence individual and institutional decision-making.

A: Could you give an example of such a lesson?

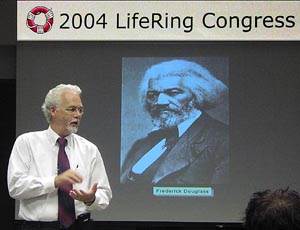

Lecture Circuit 2004

Lecture Circuit 2004

WLW: It is hard to research the history of addiction treatment without being struck by the iatrogenic insults that have been inflicted on people addicted to alcohol and drugs in the name of help. Two things are striking in this history. The first is that most of these interventions were clothed for a time in the mantle of science. In the midst of current calls for evidence-based treatment, I think this history tells us we need to carefully and continually define what we mean by evidence. The second striking fact is how hard it is to recognize such iatrogenic insults within one’s own era. We can look back with smug condescension at nineteenth century physicians prescribing pounds of cocaine to treat morphine addiction. We can self-righteously proclaim, “What on earth were they thinking?!” But it gives one pause to wonder how our own clinical policies and practices will be evaluated fifty or one hundred years from today. History is a great teacher of caution and humility.

A: It is often said that there are predictable cycles in history. Have you found such cycles and if so, what can we learn from them?

WLW: There are some predictable cycles in drug trends from which important lessons can be extracted. For example, periods of intense stimulant use in a culture are often followed by increases in sedativism, alcoholism and narcotic addiction. If that principle is true, the current methamphetamine epidemic in the US could bring narcotic addiction into rural communities that have historically not experienced this problem. In a similar vein, history tells us that the first alleged scientific reports coming out of any new drug epidemic are notoriously unreliable as are reports of miracle breakthroughs in the treatment of addiction. There are also cycles of intragenerational learning about particular drugs, but there is little evidence of intergenerational learning—a pattern that underlies the cyclical rise, demise and resurgence in particular drug choices. There is value in studying such patterns and cycles, but the problem with seeing everything within this framework is that it can blind us to patterns that are fundamentally new.

A: How did you come to collaborate on writing a history of recovery among Native American tribes?

Don Coyhis 2006

Don Coyhis 2006

WLW: That project began when I first met Don Coyhis, the Director of White Bison, Inc and leader of the Native American Wellbriety Movement. I mentioned to Don that in my research for Slaying the Dragon I had encountered bits of evidence suggesting Native American recovery circles dating to the 1730s—200 years before the founding of AA and a hundred years before the Washingtonian Revival. I suggested that this history could contribute to the cultural renewal processes that were unfolding in Indian communities across North America and encouraged him to research and write this history. He in turn challenged me to help with the project. In the course of that research, I was forced to re-evaluate everything I had been taught in my tenure in the addictions field about the historical relationship between alcohol and Native Americans. The book Alcohol Problems in Native America: The Untold Story of Resistance and Recovery [13] debunks many of the “firewater myths” that have stigmatized Indian communities and misidentified the sources of and solutions to Indian alcohol problems. Perhaps most importantly, the book details the ways in which Indian leaders resisted and continue to resist the infusion of alcohol into Native cultures, and it tells the stories of abstinence-based religious and cultural revitalization movements to contain alcohol-related problems. The process used to create this book—its oversight by Native American Elders, the use of oral tribal histories as well as archival documents, submission of a draft of the book to Native American recovery leaders—was different than anything I have ever experienced as a writer and was deeply rewarding. I am pleased that, by donating all proceeds from the book to the Native American Wellbriety Movement, we were able to break the common pattern of scholars exploiting Indian communities to further their careers without returning the fruits of their labor to these communities.

A: What additional history-related projects do you have on the drawing board?

WLW: I have three long-term projects that allow me to transmit the findings of my historical research to the field. These include my regular history columns in Counselor and in Rising: Recovery in Action (The quarterly newsletter of Faces and Voices of Recovery) and my photo history series in Addiction. The Native American recovery history project has also spawned two follow-up projects, one on the history of addiction recovery in African American communities and the other a history of addiction, treatment and recovery among American women. Each of these will require three to five more years of research and writing. My collaborators and I have already started conveying some of the history and implications from this research through the addiction counselor trade journals.

A: You publish your work in books and peer-reviewed journals, but you also invest considerable time writing for addiction treatment trade journals, recovery advocacy newsletters and writing papers that you leave in public domain and allow to be posted on multiple Internet sites.

Writing Desk 2008

Writing Desk 2008

WLW: Contributing to the scholarship of the field is important to me, but I have tried to remain faithful to my primary audiences: people in recovery, recovery advocates and those working on the front lines of treatment. There is considerable talk about knowledge transfer from research to practice and the need for education of the public and policy makers, but those of us in the research community tend to restrict ourselves to communication channels that reach each other but do not reach those who should be the ultimate consumers of our work. I think we underestimate the potential power of “grey literature,” and I’ve tried to reach my audiences through this medium. I have also enjoyed inviting many of my research colleagues to collaborate with me in this writing for “real people.”

Recovery Management

A: You have called for a recovery-focused redesign of addiction treatment. How did you come to develop this perspective?

WLW: I think of it as my epiphany in Dallas. In the late 1990s, I was interviewing a 94-year old man with 54 years of sobriety in AA about the early relationship between AA and “drying out” homes in the Southwestern United States. During a break in the interview, he asked me about this “research stuff” I did. I explained that I was part of a research institute that interviewed people after treatment and noted with some enthusiasm that we had completed some studies that had followed people for five years after treatment. He seemed amused by my pride in knowledge of such a short period of sobriety and asked what the field’s research had to say about characters like him. I thought about his 50+ years of sobriety and humbly reported that we didn’t even know he existed—that we knew next to nothing about people in such long-term recovery. I later reflected on his question a good deal and realized that my colleagues and I had spent most of our lives studying addiction and in more recent years studying this thing called treatment, but that, from the standpoint of science, we knew very little about people’s lives in recovery. It dawned on me that perhaps it was time we studied the solution to addiction that exists in the lives of millions of individuals and families. It was at this point that I began to write about switching from pathology and intervention paradigms toward a recovery paradigm as the organizing center for the field and to call for a recovery-oriented research agenda [14]. It has been exciting to see such a recovery research agenda pursued by my colleagues at the Lighthouse Institute and by researchers such as Keith Humphreys, Alexandre Laudet, Jon Morgenstern, Jim McKay and others who are illuminating the long-term recovery process.

A: This seems to have bridged into your work in what you have called recovery management. How did this work begin?

WLW: In 1998, the Illinois State Legislature funded a collaborative effort by Fayette Companies and Chestnut Health Systems to reassess the design of addiction treatment. The goal was to find more effective approaches for people with severe and complex addictions who were repeatedly cycling through the treatment system without achieving sustainable recovery. I was asked by Mike Boyle and Russ Hagen to help lead this project and began what was for me a rigorous evaluation of what treatment as currently designed can and cannot realistically achieve. The Behavioral Health Recovery Management (www.bhrm.org) project became part of a larger movement to shift addiction treatment from a model of acute biopsychosocial stabilization to a model of sustained recovery management.  Dr. Arthur Evans, Jr., Philadelphia, 2010

Dr. Arthur Evans, Jr., Philadelphia, 2010 Roland Lamb 2010 Recovery Walk

Roland Lamb 2010 Recovery Walk

Through that project, I have tried to answer two provocative questions: 1) How would we treat addiction if we really believed that addiction was a chronic disorder? and 2) How would we treat addiction if treatment professionals and treatment institutions were only paid for successful recoveries? [15, 16] This early work opened opportunities to collaborate with the efforts of visionary leaders like Dr. Tom Kirk from the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and Dr. Arthur Evans from the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health who are attempting to transform addiction treatment into recovery-oriented systems of care.

A: Addiction as a chronic disorder?

WLW: The research community is making significant contributions in helping the treatment field conceptualize addiction as a chronic disorder. McLellan and colleagues’ seminal 2000 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association will likely stand as a historical tipping point in this effort [17]. There is considerable interest in extending the current acute care model of intervention within a more time-sustained service continuum that engages people at an earlier stage of problem development and facilitates the transition from recovery initiation to sustained recovery maintenance. My colleagues and I at the Lighthouse Institute are particularly interested in the effects of post-treatment monitoring, sustained recovering coaching, assertive linkage to communities of recovery and early re-intervention on long-term recovery outcomes [18, 19].

A: One of your interests has been to map what you refer to as “the varieties of recovery experience.” Could you describe that work?

WLW: Common to my recovery advocacy work and my work in recovery management is the proposition that there are multiple pathways of long-term addiction recovery. I recently collaborated with Ernie Kurtz on a monograph that tries to convey what we know about such pathways and styles of recovery from the standpoint of history and science [20]. In this work, we plotted variations in the frameworks of recovery (religious, spiritual and secular), the scope and depth of recovery, styles and contexts of recovery initiation, and differences in recovery identity and relationships. We also tried to answer the questions of when recovery was stable and durable and whether recovery was ever completed. Our goals were to both summarize current knowledge about recovery for addiction counselors and recovery advocates and to stimulate future recovery-focused research.

A: You have also been very interested in the history of Alcoholics Anonymous and other recovery mutual aid societies.

WLW: I have been fascinated by the history of AA and pre-AA recovery mutual aid societies from Native American recovery circles of the 18th century through other early groups like the Ribbon Reform Clubs, the Keeley Leagues and the Drunkard’s Club. I have also collaborated with Ernie and Linda Kurtz on cataloguing the growth of adjuncts and alternatives to AA [21]. What I see in the international history of such groups is an unrelenting source of rebirth that emerges from the very experience of addiction. Often abandoned by family and society, people suffering from addiction have been reaching out to one another for mutual recovery support for more than 250 years. Many of the resulting groups found viable strategies of personal recovery, but very few have found a way to sustain themselves as organizations.

A: To what do you attribute AA’s growth and resilience?

WLW: There are some unique aspects to AA’s program of recovery that have contributed to its growth, but I think AA’s resilience as an organization rests not in the Twelve Steps but in the Twelve Traditions. AA groups forged unique solutions to the problems that had led to the self-destruction of earlier recovery support groups. AA found solutions to the problems of mission diversion, charismatic leadership, divisive political and religious controversies, money, property and professionalism. The Twelve Traditions of AA are the foundation of one of the most unique and resilient organizational structures in human history.

A: Your work in recovery management has led you to challenge many mainstream practices in addiction treatment. How did you come to take on the practice of administrative discharge?

WLW: At the time my colleagues and I first looked at this, 18% of all clients admitted to addiction treatment in the United States were administratively discharged, which is a euphemism for being kicked out—mostly for confirming their diagnosis via alcohol or other drug use. We have argued that administratively discharging clients from addiction treatment for AOD use is illogical and unprecedented in the health care system. There is no other sector of health care in which you can be extruded for exhibiting a symptom of the condition for which you have just been admitted. At best, this practice reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of volition in addiction and recovery. At worst, it is the endgame in a process of escalating negative countertransference. Administrative discharges can also reflect power struggles over arbitrary rules that have little if any nexus to the prospects or processes of recovery or to safety issues within the treatment milieu. We challenged this practice and offered clinical alternatives to administrative discharge [22]. Given the number of people I threw out of treatment in my early career, I consider my work in this area a form of amends.

A: You also challenged the use of “Treatment Works” as the field’s most central organizing slogan. What was your rationale for challenging this slogan?

WLW: Addiction treatment is a godsend for hundreds of thousands of individuals and families, but its role in the recovery process is misrepresented to the public through the slogan Treatment Works. I object to the slogan because it erroneously conveys the existence of a singular, static entity called “treatment” that is consistent in character and quality. The slogan fails to distinguish those individuals for whom addiction treatment is most appropriate from those who are likely to resolve AOD problems without professional intervention or who could even be potentially harmed by treatment. Perhaps most importantly, the slogan Treatment Works misrepresents the highly variable and complex outcomes of addiction treatment and shifts the focus (and responsibility for recovery) from the addicted/recovering person to the treatment professional. In my writings, I have advocated the use of alternative slogans that extol the power of personal choice and responsibility, are recovery- and family-centered and scientifically defensible, and that incorporate a menu of catalytic metaphors drawn from diverse medical, religious, spiritual, and cultural traditions. My fear is that, by exaggerating what a single brief episode of treatment can achieve, we are setting the field up for a backlash of pessimism about the prospects of long-term recovery and the value of addiction treatment as a social institution [23].

Future of the Field

A: You have warned of a coming leadership crisis in the addictions field. Describe the nature of that crisis and what we need to do to prepare for it.

WLW: First let me say this is not the first time we faced such a crisis. There were many things that led to the demise of the network of inebriate homes, inebriate asylums, and private addiction cure institutes that flourished in the United States in the late nineteenth century. The field in this earlier era suffered from a weak scientific foundation, ideological and territorial schisms, ethical abuses, unexpected economic depressions, and a rise in cultural pessimism about the prospects of addiction recovery. But in a very real sense, the field died of old age. The pioneers who had birthed and nurtured addiction treatment into professional maturity over several decades failed to deal with the problem of leadership development and leadership succession. When threats coalesced in the early twentieth century to threaten the field’s character and existence, no new generation of leaders was prepared to meet this challenge [8]. We are potentially in the same position. Long-tenured leaders of the addiction treatment field—policy makers, researchers, administrators, clinical directors and clinicians, trainers, journal editors, direct service providers—are poised to leave the field in mass in the next decade at a time the probationary status of addiction treatment as a social institution is again being questioned. We have a short window of time for leadership development and succession planning. We also need to create the infrastructure to repopulate the field with a new generation of frontline workers. I’ve been challenging all of my long-tenured peers that we cannot leave this field until we have identified and trained our replacements and found ways to leave lasting legacies of our work in this field.

A: What is your greatest fear about the future of the field?

WLW: Tom McGovern and I recently made some predictions about the future of the field with full awareness that most people who make such predictions make fools of themselves [24]. My fear is that the field of addiction treatment will disappear while an illusion of its continued presence remains. This would most likely happen by the field being colonized by more powerful forces in its operating environment—a kind of death by absorption. This happened at a micro level in the 1990s when large numbers of hospital-based addiction treatment units collapsed or were absorbed into hospital psychiatric units. In the latter cases, the hospitals continued to market the availability of addiction treatment services that for all practical purposes no longer existed. When I visited many of those units in the years following these mergers, I found little core technology of addiction treatment, only veneer-thin knowledge of the recovery process and non-existent relationships with local communities of recovery. I worry that this could happen at a more global level—that addiction treatment could be absorbed by psychiatry or become an appendage of the criminal justice system while losing the unique contributions the field has offered individuals and families suffering from addiction.

A: What are those qualities that you think historically distinguish the specialized field of addiction treatment from all the other social institutions and roles that interact with persons with severe alcohol and other drug problems?

WLW: That is the question upon which the field’s cultural legitimacy and fate rest. I don’t think there is one thing that distinguishes us, but, even with all of our internal debates, there are foundational premises of addiction treatment that distinguish us from other helping institutions. The most important of these is that severe alcohol and other drug problems are primary problems that require direct treatment. We do not believe, as allied professionals often have, that addiction is a superficial symptom of other problems and that addiction will spontaneously dissipate when the “real” problems are resolved. We believe that severe AOD problems are best resolved with assistance from those who have a deep understanding of addiction and recovery processes. We believe that these problems are best resolved in a service relationship free of contempt and that rests upon a foundation of moral equality and emotional authenticity. We contend that there are specific technologies of recovery initiation and maintenance within the addiction treatment field that are not available from other helping professionals and institutions. And we have a unique historical relationship between specialized addiction treatment and community-based recovery mutual aid societies. All manner of helping institutions and helping professions have sought to repair or respond to the consequences of addiction, but only the addiction field has focused on the morbid appetite that is the primal source of such consequences.

A: What would you consider your most significant achievement in the field?

WLW: The weak infrastructure of the field—the continued transience of the field’s organizations and workforce—make it difficult for anyone to craft a lasting legacy. In the years I worked as a national trainer, it became evident to me that the faces of the field were constantly changing and that I could never reach enough people face-to-face to leave a lasting mark on the field. It was at that point I committed myself to creating a body of work in writing and to find young people with a deep commitment to the field who I could mentor and who could carry my work into the future. If I leave a legacy, it will be in my writings and in how I have helped shape the character and skills of the field’s next generation of front line clinicians and recovery advocates. I feel I have given the treatment field in the United States the gift of its history, and I hope Slaying the Dragon will stir similar efforts to capture the history of addiction treatment in other countries.

A: In closing, how have you kept such passion for this work over the past four decades?

WLW: I’ve closely watched those people who have made sustained contributions in this field and sustained their health through that process. I have tried to model my professional life on what I have learned from them. I found four things in the lives of these professional elders: centering rituals that helped them continually refine their goals and evaluate their progress, replenishment rituals that allowed them to interact with others who shared their aspirational values, a commitment to self-development and self-care of themselves and their families, and involvement in unpaid acts of service to others. I have pursued these strategies imperfectly, but I suspect they are the source of my professional resilience. This is a field whose front lines can consume you through the losses you experience, but it is also a field that can reward you at the deepest levels. I don’t know any other helping arena within which you can witness people completely transform their lives. We get to participate in people redefining who they are at a most fundamental level, some of whom go on to lives of remarkable achievement and service to others. Staying attuned to the reality of such transformations and the potential for such transformations in all those we serve is a well of replenishment from which we should all regularly drink.

A: What fills your life outside of your professional activities?

WLW: Very simple pleasures: love for my wife and children, work in my private garden, long walks through the lush foliage and beaches near our Florida home, constant reading and donating time to grassroots recovery advocacy groups. I have traveled so much through my work that travel has rarely been a source of relaxation and pleasure for me. I am now phasing down my professional travel, and my wife and I are looking forward to increasing our visits to other countries.

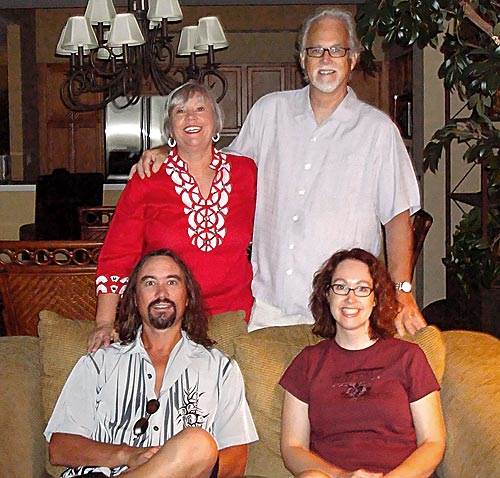

Rita and Bill with Troy and Alisha

Rita and Bill with Troy and Alisha

References

- Babor TF, Stenius K, Savva S. Publishing addiction science: A guide for the perplexed. London: International Society of Addiction Journal Editors; 2004.

- White W. The incestuous workplace: Stress and distress in the organizational family. 2nd ed. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 1997.

- Bissel L, Royce J. Ethics for addiction professionals. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 1987.

- White W, Popovits R. Critical incidents: Ethical issues in the prevention and treatment of addiction. 2nd ed. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems/Lighthouse Institute; 2000.

- Scott C, White W. Ethical issues in the conduct of longitudinal studies. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005; 28: 591-601.

- McGovern T, Babor TF, Stenius K. The road to paradise: Moral reasoning in addiction publishing. In: Babor TF, Stenius K, Savva S, editors. Publishing addiction science: A guide for the perplexed. London: International Society of Addiction Journal Editors; 2004. p. 103-120.

- White W. Voices of survival, voices of service: AIDS case management in Chicago. Chicago: AIDS Foundation of Chicago; 1994.

- White W. Slaying the dragon: The history of addiction treatment and recovery in America. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems/Lighthouse Institute; 1998.

- Kurtz E. Not-God: A history of Alcoholics Anonymous. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 1979.

- White W. Teaching addiction/treatment/recovery history: Rationale, methods and resources. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2004; 2(2): 33-43.

- White W. Let’s go make some history: Chronicles of the new addiction recovery advocacy movement (papers of William L. White). Washington DC: Johnson Institute; 2006.

- Levins Morales, A. The historian as curandera. JSRI Working Paper # 40. East Lansing, MI: The Julina Samora Research Institute, Michigan State University; 1997.

- Coyhis D, White W. Alcohol problems in Native America: The untold story of resistance and recovery. Colorado Springs, CO: White Bison, Inc; 2006.

- White W. Recovery: Its history and renaissance as an organizing construct. Alcohol Treat Q. 2005; 23(1): 3-15.

- White W, Boyle M, Loveland D. Alcoholism/addiction as a chronic disease: From rhetoric to clinical reality. Alcohol Treat Q. 2003; 20(3/4): 107-130.

- White W, Kurtz E, Sanders M. Recovery management. Chicago: Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center; 2006.

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000; 284(13): 1689-1695.

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk R, Passetti L. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002; 23: 21-32.

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R. Main findings from an experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups and early re-intervention (RMC/ERI) with chronic substance users. Eval Program Plann. 2003; 26: 339-352.

- White W, Kurtz E. The varieties of recovery experience. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care. 2006; 3(1-2): 21-61.

- Kurtz E, Kurtz L. Mutual support resources. Faces and Voices of Recovery website 2006 [cited 2006 Nov 20]; Available from http://www.facesandvoicesofrecovery.org/resources/support_home.php

- White W, Scott C, Dennis M, Boyle M. It’s time to stop kicking people out of addiction treatment. Counselor. 2005; 6(2): 12-25.

- White W. Treatment works: Is it time for a new slogan? Addiction Professional. 2005; 3(1): 22-27.

- White W, McGovern T. Treating alcohol problems: A future perspective. In: McGovern T, White W, editors. Alcohol problems in the United States: Twenty years of treatment perspective. New York: Haworth Press; 2002. p. 233-239.

Professional Appointments (2000 - present)

- Advisory Board, Recovery Advocacy Project

- Editorial Advisory Board, Journal of Recovery Science

- Advisory Committee, NAADAC Minority Fellowship Program

- Advisory Council, Faces and Voices of Recovery

- Advisory Board, Harm Reduction, Abstinence and Moderation (HAMS)

- Board of Directors, Betty Ford Institute

- National Advisory Board, Recovery Research Institute, Harvard Medical School

- NAADAC Recovery to Practice Advisory Committee

- UK National lieatment Agency Expert Group on Recovery-oriented Drug lieatment

- Advisory Panel, State of New Jersey Governor’s Council on Alcoholism & Drug Abuse

- Scientific Advisory Panel, Phoenix House, Inc.

- International Advisory Council, SMART Recovery

- Advisory Board, LifeRing Secular Recovery

- Advisory Board, Jewish Network of Addiction Recovery Support

- Advisory Council, Association of Recovery Schools

- Board of Directors, Wellbriety for Prisons, Inc.

- Editorial Board, Counselor Magazine

- Editorial Board, Student Assistance Journal

- Editorial Board, Quest House Review

- Board Member, Wired In to Recovery, UK

- Editorial Board, Alcoholism lieatment Quarterly

- Editorial Board, Advances in Addiction and Recovery

Professional Awards

| |

Year |

Award |

|

1999 |

McGovern Family Foundation Award for the best book on addiction recovery for Slaying the Dragon |

|

2001 |

Keith Keesy Memorial Award presented by the Illinois Association of Alcohol and Drug Dependence |

|

2001 |

President’s Award, NAADAC—The Association for Addiction Professionals |

|

2002 |

Lifetime Achievement Award, Illinois Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Professional Certification Association (IAODAPCA) |

|

2003 |

National Association of Addiction Treatment Provider’s (NAATP) Michael Q. Ford Journalism Award |

|

2004 |

National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD) Award for Compelling Documentation of the Alcoholism Movement in the United States |

|

2006 |

Eagleville Award—an annual award presented by Eagleville Hospital to a person who has made a significant contribution to the field of addiction treatment. |

| |

2006 |

Lifetime Achievement Award presented by NAADAC—The Association for Addiction Professionals |

|

2006 |

Jeff Luke Servant Leadership Award presented by White Bison for service to the Native American Wellbriety Movement |

|

2007 |

John P. McGovern, M.D. Award presented by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) for outstanding contributions to the field of Addiction Medicine |

|

2009 |

Lifetime Achievement Award, Mayor’s Drug and Alcohol Executive Commission, City of Philadelphia |

|

2010 |

Dr. Nelson J. Bradley Life Time Achievement Award, National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers |

|

2010 |

The John P. McGovern Award and Lecture, Institute for Behavior and Health, Inc. |

|

2010 |

Recovery Award for Excellence in Addiction Research & Education, Foundation for Recovery |

| |

2011 |

Recovery Heroes Honoree, NET Institute-Center for Addiction & Recovery Education |

|

2012 |

Norman E. Zinberg Award & Memorial Lecture, Harvard University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry |

|

2012 |

Friend of the Field Award (for extraordinary contributions to the field of opioid addiction treatment), American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence |

|

2012 |

Lifetime Achievement, The Voice Awards, Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration |

|

2013 |

Saul Feldman Award for Lifetime Achievement for sustained and significant contributions to leadership and policy in the mental health and addiction recovery field. ACMHA The College for Behavioral Health Leadership |

|

2013 |

Resolution of commendation for sustained and seminal contributions to the addiction treatment and recovery field, Board of Directors, The Illinois Alcoholism and Drug Dependence Association |

|

2013 |

Distinguished Advocate of the Year Award, Texas Association of Addiction Professionals |

|

2015 |

Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award, America Honors Recovery / Faces and Voices of Recovery for outstanding contributions and lifetime devotion to the recovery advocacy movement. |

|

2015 |

William L. White Lifetime Achievement Award for the Advancement of Recovery Research (year one recipient of named award). Young People in Recovery & Association of Recovery Schools. |

| |

2018 |

William White, Non-African American Contributors to African American Recovery. Online Museum of African American Addictions, Treatment and Recovery |

Awards Named for William White

- William L. White Scholarship Award (Granted annually since 2015 by NAADAC: The Association for Addiction Professionals)

- The William White Life Time Achievement Award. (Granted annually since 2015 by the Illinois Chapter of NAADAC)

- William L White Lifetime Achievement Award for the Advancement of Recovery Research (Jointly granted annually since 2015 by Young People in Recovery and Association of Recovery Schools)

- William L. White Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award (Granted annually since 2016) by America Honors Recovery / Faces and Voices of Recovery

Participation in Documentary Film Projects

- Memo To Self: Protecting Sobriety with the Science of Safety (Dr. Kevin McCauley, The Institute for Addiction Study)

- The Anonymous People (4th Dimension Productions, LLC)

- Bill W. (Page 124 Productions)

- Moyers on Addiction: Close to Home (Bill Moyers PBS special)

- Robert Zemekis On Smoking, Drinking and Drugging in the 20th Century (Showtime)

- Addiction Project (HBO, consultant and writer)

- Betty Ford: A Legacy of Hope (Betty Ford Center)

- The Healing Power of Recovery (Connecticut Community of Addiction Recovery)

- Philadelphia Recovery liansformation (Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health)

- Reflections: Ernie Kurtz on the History of A.A., Spirituality, Shame and Stoytelling—with Bill White (Great Lakes Addiction Technology liansfer Center)

- ROSC: Recovery-oriented Systems of Care (with Ijeoma Achara, Southeast Addiction Technology liansfer Center)

Co-authors

One of the foundational concepts of addiction recovery is that achievements are possible in collaboration that would not be possible in isolation. That principle has guided my professional as well as personal life. Much that I have been able to learn and contribute is due to those with whom I have co-authored papers, monographs, book chapters and books and to those who agreed to collaborate with me on published interviews. I wish to extend my deepest appreciation to the following co-authors for their openness to such collaborations and for their invitations to me to participate in their own projects.